Explore the Binjareb-Peel Geotrail Drive

The geotrail drive in the Peel Region is a great way to explore the geological, natural and cultural highlights of the area.

This driving trail can be completed in one day, or if you explore inbetween the geotrail sites you can spread this drive trail over 2 days or a weekend.

Learn about the Geology, Biotic ( Flora and Fauna), and Culture ( Indigenous and European History) of the coastal Peel Region.

To download the map to the drive trail, please click here or access the google map of the trail here

The sites are listed below and can be accessed in any order.

- All

- Peel GeoDrive Trail

Mandurah Visitor Centre

Information Stop to gather maps, and learn about other attractions and activities in the local area.

This is a great place to get a brochure for your Geo Drive Trail.

Located near by are restaurants, bars, coffee shops, boat cruises and shopping

From Mandurah’s Visitor Centre, proceed to the viewing platform overlooking the Mandurah Channel Entrance.

From this site, you will have views of where the Peel Estuary meets the Ocean.

Click the sections below to learn about this area’s Geology, Biotic Life ( marine and bird life) and the Culture and History of this location.

Geology

The Mandurah Channel Entrance:

The meeting point of the Peel Estuary to the Indian Ocean.

What is an Estuary?

An estuary is located at the mouth of a river, where tidal effects are evident, and where river and seawater meet. Estuaries are interesting because they represent the meeting of several different environments: the land, the river, and the sea.

The channel of the Peel Estuary is the outlet for three rivers – The Serpentine, Murray and Harvey Rivers. The Peel – Harvey Estuary is the largest estuary system in South West Australia.

The Peel Estuary is a Basin Estuary and connects to the Harvey Estuary which is an inter-barrier estuary that lies behind the spearwood dune system. The Peel-Harvey Estuary is 134 square km – twice the size of Sydney’s Darling Harbor. However the Peel Estuary is very shallow and only 2m at the deepest in the middle of the Peel basin.

The catchment is the area of land where water flows through rivers and underground aquifers to reach the estuary. The Catchment of the Peel-Harvey Estuary is 12,000 square km – that is bigger than Jamaica and also bigger than the country of Luxumburg. Water tfalls on the Wheatbelt town of Williams ( 150 km East of here) will make it’s way via rivers and creeks to the Peel -Harvey Estuary and then out the mouth of this channel entrance.

The Mandurah Channel Entrance is 5km long and is dredged to 2m deep.

Geological Setting:

Peel Harvey Estuary is composed of layers of sediments that were deposited by rivers and seas and sculpted by winds during the last 10,000 years since the most recent Ice Age. The rising sea levels (around 8,000 years ago) that followed the melting of the ice caps flooded old river valleys forming the Peel-Harvey Estuary.

The Peel Estuary lies inbetween the Spearwood Sanddune in the west and the slightly older Bassendean Dunes to the east. The bottom sediments of the estuary contain marine shells from 4000 to 5000 years ago.

Before humans intervened, the Mandurah Channel Entrance was a delta system with a large network of sand spits and vegetation. This would not open to the ocean, unless there was a strong rains and water flow coming down from the rivers. Then the mouth of the estuary would break open and connect to the Ocean.

The Mandurah Channel entrance is also impacted by the northwards longshore drift of sand in the Indian Ocean. This means there is constantly sand moving infront of the Mandurah Channel entrance that needs to be dredged to ensure it stays open to the ocean. In 1985 a proposal to continually dredge the channel entrance was adopted by the State Government ( See Culture/ History section).

In 2021 – 220,000 cubic meters of sand is pumped from the Halls Head Beach in the south to Town Beach on the northside of the channel entrance, it took 5 months to move this amount of sand.

If you would like to learn more about the Geology of the Mandurah Channel Entrance visit this Page

References:

A. Brearly 2005 p. 1

G. Seddon 1972 p. 5

Biotic

Marine Species

Fish:

Over 70 species of fish have been identified in the Peel-Harvey estuary.

Common species include:

- yellow-eye mullet,

- sea mullet,

- cobbler,

- King George Whiting,

- Taylor,

- black bream,

- sea garfish

- skipjack (Trevally)

- blue mana crab

- river prawn

- Western King prawn

- mulloway

- Western river garfish

How do fish and shellfish use the estuary?

Fish using an estuary can be divided into four categories,

Marine Stragglers: these fish live in breed in the ocean and use the estuary as a feeding area for maturing or mature adults. They generally stay close to the estuary entrance, where the salinity is similar to the ocean. These fish are generally caught near the bridge at Mandrah. ( Tailor, Garfish, Herring)

Nursery Habitat: Use the estuary as a nursery habitat for juveniles, but usually spawn at sea. ( Yellow-eye Mullet, striped trumpter, blue manna crab, king prawn, river prawn, cobbler, whitebait )

Etuary Dependent: These fish use the estuary for their entire life cycle. ( Hardyhead, Black Bream, Yellow-finned whiting)

Anadromous Species: Migrate from the sea to the estuary to breed in reduced salinity. (This category is uncommon in the Peel-Harvey Estuary).

The Peel-Harvey blue swimmer crab fishery is an important fishery as it is the world’s only Marine Stewardship Council certified commercial and recreational fishery (Marine Stewardship Council, 2016). Close to 100 tonnes of crab a year is landed by commercial fishers, all of which is sold locally, and similar amounts are caught by recreational fishers ( this is estimated as there are no recreational licenses for Blue Manna Crab, but there are catch limits: minimum size 127mm, Closed to all crab fishing 1 September to. 30 November, bag limit 10 crabs allowed per person, boat limit – 20 crabs.

There is also a Grey Mullet commercial fishery in the Peel-Harvey Estuary which are caught with Gill nets or Mesh nets.

Dolphins: The Peel-Harvey Estuary has a population of approximately 90 Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins. These dolphins are apex predators and collectively catch over 200,000 kg of fin fish from the estuary. In the Mandurah Channel Entrance and town waters there is a sub group of bottlenose dolphins. Some of the Adult females are recorded in the Fin Book which categlogues the dolphins based on their dorsal fin.

Keep and eye out for these distinctive fins:

Nicky – Female – has had 6 calves since 2009. Christmas – Female (Nicy’s daughter) Top notch – Female – has had 3 calves

Bird Life:

The Peel-Harvey Estuary system is recognised internationally for it’s importance to a diverse range of bird life.

Around the Mandurah Channel Entrance look out for waterbirds – Commerants, Datars, Egrets, Pelicans, Ducks, Black Swans, Terns and Silver Gulls

(more information about the Peel-Harvey Estuary Birdlife is found throughout the Geodrive trail sites.)

Other Biotic life at this site:

Green Sea Turtles can sometimes be spotted at the channel entrance

Stingrays can also be seen in this area

The estuary fringes have changed overtime, and now this area has man made rock groins that have replaced the saltmarshes of the delta system that would have been here before development.

Culture

Indigenous Heritage Investigation of Aboriginal use of the Mandurah Inlet reveals evidence of Aboriginal activity and stories associated with the area. A range of sites have been identified which reflect the diverse use of the area including ceremonial, camp, artefacts, burial, and mythological sites. The area is located near the junction between the Whadjug and Bindjareb tribes of the Nyungar people (O’Connor et al., 1989). The Peel Inlet itself contained a number of Aboriginal camping grounds, and a freshwater spring, the location of which is no longer known (O’Connor et al., 1989). The inlet and associated wetland areas of the region were intensively occupied as a result of the fresh water and food resources they provided. The coastal inlet area was important to the Aboriginal people, yielding potential for hunting, gathering, and fishing with many indigenous plants consumed for food and medicine. The Department of Indigenous Affairs Site Register reveals several sites which potentially occur within the study area.

For further information: https://www.mandurah.wa.gov.au/-/media/files/com/downloads/community/services/planning/reports/report-volume-2-context-analysis.pdf and https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2020-12/Peel_Harvey_Estuary_Protection_Plan_Bindjareb-Djilba.pdf

Modern History

The Mandurah entrance channel has undergone a considerable amount of change since 1887, when the first efforts were made to modify it.

By the later part of the century Mandurah had become the service center for a small agricultural community and a popular holiday resort. Even at this early stage of development residents, visitors and the government alike were concerned by problems associated with the ocean entrance, particularly its migratory nature and the adverse effects of frequent closures on the estuary water quality and fish populations.

Petitions were made to the state government to improve the entrance and available records show that the earliest river training work was undertaken in the 1880s when a wall was constructed around Stingray point where the Peninsula Hotel now stands to ensure the channel kept to the west of this location.

The construction of a second training wall commenced in 1939, with the main purpose being to promote a better opening to the ocean and protect an area of land used by campers. Nevertheless, the entrance was still often closed, and attempts to cut channels to the ocean were not always successful.

A dredger was used in 1959 to open the entrance channel through the bar at its western. A secondary benefit some foreshore land was reclaimed for recreation and camping purpose on the eastern side of the entrance channel.

The entrance channel shallowed rapidly and within 18 months had closed and stayed closed during the period from 1967 to 1969. Two training walls were constructed in 1970. The training walls helped to prevent the ocean entrance from being closed by literal sand drift.

However, as the entrance channel Mandurah is situated on a sandy coastline on which there is a large wave induced literal sand drift, dredging of the channel is still required to maintain the entrance channel in optimum condition.

Without dredging part of the littoral drift sand which reaches the entrance is carried into the inlet by flood (incomming) tides to be deposited within the inlet channel at slackwater. During ebb (outgoing) tides a portion of the sand is carried back out to the ocean and deposited offshore from the entrance or carried down t from the entrance by wave action. These sand deposition sites are termed the inner and outer shoals or bars.

In 1985, the government announced approval of an ongoing dredging project. 2020-2021 was the largest dredging program ever undertaken. 200,000 cubic meters of sand was pumped from the Eastern to the Western side of the channel entrance.

Commerical fishing and recreational boating use the channel entrance and allow access to the protected estuary waters.

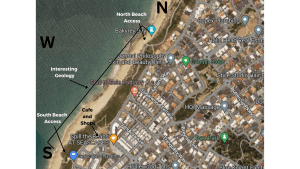

SeaScapes is a part of the Halls Head suburb of Mandurah. Follow the directions (Here) to reach this coastal location.

You have the option to stop at the local shops, which include a cafe, grocery store, and fish and chip shop.

There are two entrance points. The northern entrance is recommended for all access with a ramp leading to the beach.

The best hightide viewings are from the northern entrance.

The southern entrance has public toilets and stairs leading down to the beach.

There is only on-street parking available at this site.

Geology

Current shoreline of Halls Head and Seascapes. This site is interpreted as the southern extension of the Garden Island

Ridge which intersects the coastline at Halls Head (Semeniuk, 1995), and continues further south inland as the

Mandurah Eaton Ridge. The coastal cliffs and outcrops represent the Pleistocene aeolian calcarenite Tamala limestone

which is overlain by the Quaternary Quindalup sand dunes. Features present include shoreline platforms, wave cut

notches and splash zones, cross-cutting bedding, paleosol horizons, rhizolith fossil root structures, solution pipes, karst

formations, and calcrete layers. The processes of erosion including physical, chemical and bioerosion can be witnessed

along the shoreline.

Biotic

Flora ( Plants)

The Vegetation along the coastline at Sea Scapes is tough! It grows in the Quindalup Soils. The unique flora and fauna found in the dunes provide important ecosystem services, including soil stabilization and nutrient cycling. These local native plants have no problems living with our nutrient-poor sandy soils.

They have adapted to grow successfully and flower brilliantly in very poor soil conditions. The adaptations of local native plants include:

- leaf shape and size;

- leaf composition;

- modified root systems;

- they go dormant over summer; and

- nutrients from other sources (such as insectivorous and parasitic plants).

Can you spot any of these plants?

-

Leucopogon parviflorus (Coastal Beard-heath): a small shrub with small white flowers that grows in sandy soils.

Leucopogon parviflorus (Coastal Beard-heath): a small shrub with small white flowers that grows in sandy soils.  Spyridium globulosum ( Basket Bush): has leaves that are green on the outside and almost white on the underside. Dead leaves are yellow in appearance. Abundant tiny flowers are produced in winter.

Spyridium globulosum ( Basket Bush): has leaves that are green on the outside and almost white on the underside. Dead leaves are yellow in appearance. Abundant tiny flowers are produced in winter. Conostylis candicans (Grey Cottonheads): a herb with small, greyish leaves and yellow flowers that grow in dense clusters.

Conostylis candicans (Grey Cottonheads): a herb with small, greyish leaves and yellow flowers that grow in dense clusters.

Fauna (Animals)

- Bobtail Lizard: This slow-moving lizard is often seen basking in the sun in the dunes and surrounding areas.

- Grey Fan-tail (Rhipidura albiscapa): is a small, insect-eating bird. It is known for its distinctive tail, which is constantly fanned and twisted as the bird flits through the air, catching insects in flight. They are also known for their curious and inquisitive behavior, and will often approach humans to investigate.

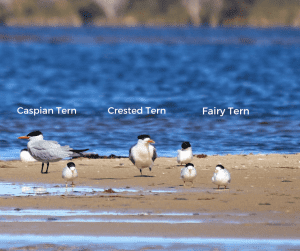

- Terns: Caspian, Crested and Fairy Terns are seabirds that you will see flying along the dunes and shoreline looking for food. Below are photos of these three species from largest ( Caspian Tern) to the smallest ( Fairy Tern).

Culture

This area is registered as a Binjareb indigenous heritage site. There have been archeological assessments of this site that show occupation evidence, and also this coastal region has been registered as an indigenous burial site. The studies completed in this area show the significant occupation by the Binjareb people along this coastal stretch.

Use of sea was considered important to Noongar people. Marine resources including spearing of seals, camping along the coast

to fish, which was important to the family economy. There are a number of fish traps known along the coastline. The claimants

tell stories of dolphins and whales being family ‘totems’.

The Seascapes area provided ample sources of fish and shellfish depending on seasons. Salmon and sea mullet from the sea as well as mussells and abalone from the reefs. These resources were also used for trading with family groups that came down from the Darling Scarp.

European History:

Halls Head is named after Henry Hall who was granted land in the area in the 1830s. The suburb was officially named in 1970, but had been locally known by the name for some years previously.

Travel from Seascapes to the Dawesville Cut. You will be visiting the South East Side of the Channel.

Here is the best viewing point

From here you can see where the Peel Estuary Basin meets the Harvey Estuary and also where the channel has been made by man to connect to the ocean. This is a very productive region. Keep an eye out for the Dawesville Cut Dolphins.

Geology

The cut is approximately 1.8 kilometers long, 120 meters wide, and 2 to 3 meters deep, and was excavated through a sandy barrier that separates the estuary from the ocean. The construction of the Dawesville Cut and Channel began in 1994 and was completed in 1995.

During the construction of the Dawesville Channel and Cut, large amounts of sand and sediment were dredged from the estuary and deposited in nearby areas, including the beach at Port Bouvard. This has had an impact on the local geology, as the sediment has altered the natural flow of water and the deposition of sediment in the area.

At the Ocean end it was expected that Longshore drift would impact the entrance to the Dawesville cut, in the same way, the Mandurah Channel Entrance is impacted by longshore drift and sediment buildup. Dredging of sand is a regular occurrence to keep the channel open.

Two rock groynes were established on the Ocean side to prevent the fast build-up of sediments.

Biotic

The Dawesville Cut is home to a diverse range of marine life, including fish, crabs, mollusks, and other aquatic animals. The increased water flow and improved water quality in the Peel-Harvey Estuary that resulted from the construction of the cut has led to an increase in the populations of some species.

Fish species that are commonly found in the Dawesville Cut include herring, whiting, flathead, bream, tailor, and salmon. These species are attracted to the area due to the increased water flow, which provides a more favorable habitat for feeding and breeding.

Crabs are also abundant in the cut, with blue swimmer crabs being a popular catch for recreational fishers. Other species of crabs, such as sand crabs, can also be found in the area.

Mollusks, such as oysters and mussels, can be found in the estuary and along the shoreline of the cut. These species help to filter the water and improve the overall health of the ecosystem.

In addition to these species, the Dawesville Cut is also home to a variety of other aquatic animals, including dolphins, sea turtles, and various species of seabirds.

Keep an eye out for Dolphins in the Dawsville Cut.

Culture

Prior to the artificial Dawesville Cut being established in 1994, Aboriginal groups walked across the land on treks north and south.

The deteriorating environment of the Peel-Harvey Estuary became a major political and environmental issue for the

Government of Western Australia during the mid-1980s.

The channel’s construction commenced in 1990 and was completed in April 1994 at a cost of $76 million. It is 2.5 km long,

200 meters wide and between 6 and 6.5 meters deep.

As part of the construction, a sand trap immediately to the south of the sea opening was incorporated into the design, to capture sand build-up from the natural south to north movement along the coast caused by the prevailing south-westerly winds. If the sand was not captured and mechanically moved, the channel would quickly silt up, because there is insufficient water flow through the channel to compensate for the build-up. Approximately 85 thousand cubic metres of sand per year is mechanically moved from the south to the northern side of the

channel.

From the Dawesville Channel Entrance drive along Estuary Dr to Warrungup Springs.

The springs are an important geological, ecological, and cultural site, as they support a range of plant and animal species and have significant cultural importance to the local Indigenous people, and have Karst geology that allows the springs to come through to the surface.

Geology

Warrungup Springs is a special place located on the eastern slope of the Mandurah Eaton ridge and the western shoreline of the Harvey Estuary. The geology of this area has exposed Tamala limestone that has special features called karst. There is also a freshwater spring that deposits along the shoreline of the estuary.

Underneath the Mandurah-Eaton ridge, there is an aquifer made of a type of sand called the Eaton sandunit. This aquifer is important because it stores and moves groundwater, which is recharged when it rains and through the special features in the ridge called karst. The karst features allow water to seep into the aquifer, like a sponge.

Water from the aquifer flows out at places called discharge sites or springs. These are found at the bottom of the ridge and along the shoreline of the estuary. This site is all about the rocks and groundwater in the area and how they interact with each other.

Biotic

The Warrungup Springs area is home to a diverse range of flora and fauna, with many species that are adapted to the local environment.

The vegetation around the springs includes a mix of Banksia and Tuart woodlands, it then leads to saltmarshes with saltwater paperbarks. There is wonderful understory species like Templetonia and a variety of orchids, however these have been taken over by weeds since the last fire in the area.

There are many animals that call the Warrungup Springs area home, including reptiles such as western bearded dragons and bobtails, and birds such as Splendid Fairy Wrens, red-tailed black cockatoo and the Eastern Ospreys. The freshwater springs support a range of aquatic species, including stingrays, fish, and crustaceans. You can also spot the Harvey River Bottlenose dolphins from this point at times.

Culture

Warrung Springs is also known as Yoka Maya a significant cultural site located near Warrungup Springs, along the Western side of Peel-Yalgorup Wetlands system in Western Australia. This site holds great cultural and spiritual significance to the local Noongar people of the Bindjareb group.

As the source of fresh water it provided for Aboriginal groups who traveled along the estuary edge.

Please see the cultural trail information The Bilya Country Story Trail Map for this site. The Cultural Trail information matches many of the Geotrail drive site.

The White Hills Rd. Lookout offers a clear uninterrupted view of the Yalgorup Landscape, which makes it possible to see the geological setting on a big scale. This is useful for studying and understanding the geology of the area. You can see several geological features from this vantage point, such as the Bouvard Reefs, the Quindalup dune system, the Tim’s Thicket limestone, the Yalgorup plain, the Mandurah-Eaton ridge, Lake Clifton, and the Darling Scarp. These features provide valuable insights into the geological history and formation of the area. Read more Below.

Geology

Geological Features of the Landscape:

- The Bouvard Reefs – These are rocky structures that are found along the coast. They were formed by the accumulation of shells and other marine organisms over a long period of time.

- The Quindalup dune system – This is a series of sand dunes that run along the coast. They were formed by wind and wave action, and they are constantly changing shape and position.

- The Tim’s Thicket limestone – This is a type of rock that is made up of compressed shells and other marine organisms. It was formed over millions of years by the accumulation of these organisms on the ocean floor.

- The Yalgorup plain – This is a large flat area of land that is covered in grasses and other vegetation. It was formed by the accumulation of sediment over a long period of time.

- The Mandurah-Eaton ridge – This is a long, narrow ridge of land that runs parallel to the coast. It was formed by the movement of tectonic plates, and it is made up of a variety of rock types.

- Lake Clifton – This is a large, shallow lake that is home to a unique type of microorganism called Thrombolites. These organisms create limestone rock dome structures that can be seen along the edge of the lake.

- The Darling Scarp – This is a steep hillside that runs parallel to the coast. It was formed by tectonic activity, and it is made up of a variety of rock types. The Scarp is an important geological feature in Western Australia, and it has played a significant role in shaping the landscape and ecosystems of the region.

Biotic

From this viewpoint you can see various ecosystems.

Coastal Heathland:

Coastal heathland ecosystem in Mandurah is a type of ecosystem that is found along the coastline of the region. It is characterized by a diverse range of low-growing, woody shrubs, as well as grasses, herbs, and small trees. These plants are adapted to the harsh coastal environment, which is characterized by sandy soils, high winds, and salt spray.

Some of the common plant species found in the coastal heathland ecosystem in Mandurah include the coastal wattle, banksia, tea-tree, and hakea.

The coastal heathland ecosystem is also home to a range of reptiles, such as skinks and snakes, as well as amphibians, such as frogs. Many bush birds love this environment and can be seen.

Some of the common bird species found in this area include:

- Western whipbird – a medium-sized bird with a distinctive call that is often heard in the early morning.

- White-cheeked honeyeater – a small bird with a distinctive white cheek patch and a sweet, melodic call.

- Grey fantail – a small bird with a long, fanned tail and an active, flitting flight pattern.

- Rufous whistler – a medium-sized bird with a beautiful, musical song.

- New Holland honeyeater – a small bird with a distinctive black and yellow coloration and a buzzy, energetic call.

- Splendid fairy-wren – a small, brightly colored bird that is often seen flitting through the low shrubs and grasses.

These bird species play an important role in the coastal heathland ecosystem, providing pollination services, controlling insect populations, and dispersing seeds. The diversity of bird species in this area is a testament to the ecological richness of the coastal heathland habitat.

The coastal heathland ecosystem is an important part of the region’s natural heritage, providing a range of ecological services, such as erosion control and water filtration. It is also valued for its aesthetic qualities, with its striking mix of plants, textures, and colors providing a beautiful backdrop to the coastline. However, like many ecosystems around the world, the coastal heathland ecosystem in Mandurah is under threat from factors such as land clearing, invasive species, and climate change. Conservation efforts are underway to protect and restore this unique ecosystem for future generations to enjoy.

Balga Groves:

A grove of Xanthorrhoea Pressii refers to a group of trees that belong to the Xanthorrhoea genus, commonly known as grasstrees or in the past called blackboys. Xanthorrhoea Pressii is a species of grass tree that is endemic to the southwest of Western Australia.

A grove of Xanthorrhoea Pressii is typically characterized by a collection of tall, slender stems with a bushy tuft of grass-like leaves at the top of each stem. These stems can range in height from a few meters to over ten meters tall, and they often grow in dense clusters, creating a distinctive and striking landscape.

Xanthorrhoea Pressii groves are usually found in sandy or rocky soils, in areas that have a Mediterranean climate with warm, dry summers and cool, wet winters. They are important ecological features, as they provide habitat and food for a range of native animals, such as birds, insects, and small mammals. During their flowering season the tall stalks that grow are filled with thousands of nectar-rich flowers that insects, birds and even possums love.

Tuart Woodlands:

A Tuart Woodland is a type of woodland ecosystem that is dominated by the Tuart tree (Eucalyptus gomphocephala), a tall and majestic eucalyptus species that is endemic to the Swan Coastal Plain of Western Australia.

In addition to the Tuart tree, a Tuart Woodland ecosystem is typically characterized by a diverse understory of shrubs, grasses, and wildflowers. These include species such as Banksia, Hakea, Acacia, Grevillea, and Xanthorrhoea, which are adapted to the dry, sandy soils and Mediterranean climate of the region.

Tuart Woodlands are typically found in the coastal regions of Western Australia, they are the Eucalypt that grows closest to the West Coast. This is because this tree grows on limestone and the calcium carbonate environment suits it.

Tuarts play an important ecological role in supporting a wide range of native plant and animal species. They are also important for the conservation of biodiversity, as they are home to many species that are not found anywhere else in the world. Large Tuarts act as a hotel for marsuipals, reptiles, birds and a variety of insects.

Tuart Woodlands are considered to be a Threatened Ecological Community (TEC) in Western Australia, due to the threats posed by urbanisation, land clearing, and changes in fire regimes. As a result, there is a need to protect and conserve these ecosystems, in order to maintain the unique biodiversity of the region and to ensure the long-term sustainability of the ecosystem.

Indian Ocean:

an important marine ecosystem located off the coast of Western Australia. It is a complex system of shallow coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and sandy bottom habitats that support a wide range of marine life. Some of the key features of this ecosystem include:

- Limestone reefs – The Bouvard Reefs provide habitat and shelter for a diverse array of fish and invertebrates.

- Seagrass meadows – Seagrass beds in the Bouvard Reefs ecosystem provide important feeding grounds and nursery areas for many fish and other marine animals. They also help to stabilize sediments and maintain water quality by filtering pollutants.

- Sandy bottoms – These habitats provide important feeding and resting areas for bottom-dwelling fish and invertebrates, such as sand crabs and flatfish.

- Marine megafauna – The Bouvard Reefs are home to a variety of larger marine animals, including dolphins, sharks, and rays.

- Threatened species – The Bouvard Reefs ecosystem is also home to several threatened or endangered species, such as the Western Australian seahorse. The Loggerhead turtle has also been seen in this area and is endangered.

Culture

The Binjareb Indigenous people have a deep connection with the coastal environment around Yalgorup. They used the land and sea for a range of purposes, including food, shelter, and cultural practices. The hill was also used as a lookout to see other campfires and know the location of other Aboriginal groups.

Some of the ways they used the coastal environment include:

- Fishing: The Binjareb people were skilled fishermen and used a range of techniques to catch fish, including spearing, trapping, and netting. They caught a variety of fish species, including bream, mullet, and herring.

- Gathering: The coastal environment provided an abundance of plant and animal resources, including shellfish, crabs, and seaweed. The Binjareb people collected these resources for food and medicinal purposes.

- Cultural practices: The coastal environment was an important part of Binjareb culture and spirituality. They conducted ceremonies and rituals in coastal locations.

Island Point Reserve is a natural reserve located in Mandurah, Western Australia. The reserve covers an area of approximately 65 hectares and is characterized by a diverse range of ecosystems, including coastal heathlands, tuart woodlands, and wetlands. The reserve is situated on a narrow strip of land between the Indian Ocean and the Peel Inlet and is home to a variety of flora and fauna, including rare and endangered species.

Geology

Island point reserve sits on the eastern side of Mandurah-Eaton Ridge.

The Mandurah-Eaton Ridge is a long, narrow sand and limestone ridge that extends north-south through the Peel region of Western Australia. It is primarily composed of Tertiary-aged sedimentary rocks, including the Tamala Limestone, the Kondinin Formation, and the Yarragadee Formation.

The Tamala Limestone is a pale-colored, fossil-rich limestone that forms the uppermost layer of the ridge. The Kondinin Formation is a sandstone and shale unit that underlies the Tamala Limestone and is known for its distinctive pink and green coloration. The Yarragadee Formation is a deeper, more poorly exposed unit composed of sandstone and siltstone.

The Mandurah-Eaton Ridge was formed during the Paleocene and Eocene epochs, between 66 and 34 million years ago, as a result of tectonic uplift and subsequent erosion by wind and water. The ridge is an important hydrogeological feature, containing several aquifers that provide water to the surrounding region. It also supports a diverse range of flora and fauna adapted to the unique geology and soil conditions of the area.

Biotic

Island Point Reserve is a 70 hectare bushland reserve that is located near the Harvey Estuary. It is home to four different ecosystems, which include peppermint dominant woodland, banksia mixed woodland, temperate saltmarsh, and sedgeland environments. The reserve has many tree species, such as Marri, Jarrah, Tuart, Peppermint, and Banksia Woodland, and a diverse understory. There are 62 species of native orchids that have been recorded in this reserve. The reserve is also home to a critically endangered Western Ringtail Possum population, with 29 individuals being sighted during a survey. Other animals that can be found in the reserve include Brushtail possums, Brush-tailed Phascogale, Western Grey Kangaroo, Bush birds, waterbirds, and birds of prey. An active osprey nesting platform can be found adjacent to the estuary. Island Point Reserve is a great place to see a variety of wildflowers and to go birdwatching.

Culture

Island Point Crossing was a major link between the west and east of the Peel-Harvey Estuary. It was a significant crossing point for Aboriginal people who camped in the area. Camping areas are identified at the Southern End of Island Point Reserve.

The crossing was also an old stock route from Pinjarra to Bunbury over the Harvey Estuary. Many settlers in the southern section of Mandurah relied on the crossing. Every 6 months the cattle had to be shifted from inadequate coastal grazing areas to grazing areas further inland to avoid “coastie disease” (State Heritage No. 09069).

Island Point reserve has a freshwater source and this area was relied upon for camping also a diverse source of bush tucker is available throughout the reserve (Yates, 2005).

This thrombolite reef system is one of the world’s largest living microbialites reefs.

Geology

Thrombolites are a form of microbialite – structures formed by photosynthetic microbes that precipitate calcium carbonate (limestone). Microbialite structures are evidence of the oldest life on Earth and are of great scientific interest. The cyanobacteria present in ancient stromatolites are a likely source of increased levels of oxygen in the atmosphere 2200 to 2400 million years ago.

Western Australia contains a rich microbialite fossil record as well as the greatest number and most varied types of living microbialites in the world. This site provides valuable evidence on the nature of historic environments, aiding in the interpretation of the Earth’s earliest biosphere (Moore, 1993). Lake Clifton supports the largest known examples of living nonmarine microbialites in the southern hemisphere. Radiocarbon dating indicates that the Lake Clifton thrombolites began to form up to 1950 years ago (Moore and Burne 1994).

Seasonal fluctuations in the Lake Clifton water levels expose the Thrombolites in summer and submerge them during winter. Complex abiotic interactions occur with the surface water and groundwater chemistry, lake sedimentation, wind patterns and climate, all influence the Thrombolite community. Lake Clifton was the first place in the world where modern thrombolites were scientifically compared with modern stromatolites. (Burne &

Moore, 1987).

The first published report on the organosedimentary features at Lake Clifton was made in 1912. In 1979 L. Moore recognised the occurrence of ‘stromatolites’ on the foreshore of the Lake.

Biotic

The Thrombolites are formed by a complex community of micro-organisms including cyanobacteria precipitating calcium carbonate from fresh groundwater seeping up from underground aquifers.

The metabolic activity of the microbes relies on sunlight for photosynthesis and the supply of calcium-rich groundwater for growth.

Microbial mats grow on the Lake floor. Diverse metazoan fauna living within the reef structure.

Culture

The Thrombolites hold a significant place for the Noongar people in their Dreamtime stories of creation.

Woggaal Maadjit’s Noorook:

The nest of the rainbow serpent and the Thrombolites represent the eggs laid by the serpent.

“One day the Aboriginal people of the Mandurah area found there were no waterways, they went to the beach and danced and sung for the great Waugal to come. Then she came and started to make the Peel Inlet and the estuary, she found that she was carrying eggs and she rested in between the estuary and the sea until she laid them. Then the eggs hatched and she sent her babies to do the rest of the work because she was tired. She sent one up the Serpentine, one up the Murray and one up the Harvey and that’s how they came to be” – Story told by Gloria Kearing (DWER, 2022).

The Lime Kiln is located adjacent to the Lake Clifton Thrombolites which are Ramsar-listed wetlands and a TEC ( threatened ecological

community).

It is within the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions Yalgorup National Park and the Shire of Waroona.

Geology

Peel Harvey Estuary is composed of layers of sediments that were deposited by rivers and seas and sculpted by winds during the last 10,000 years since the most recent Ice Age.

The rising sea levels (around 8,000 years ago) that followed the melting of the ice caps, flooded old river valleys forming the Peel-Harvey Estuary.

Culture

There is little recorded history of Aboriginal use of the area however, Aboriginal family groups may have used the lakeside access as pathways for travelling north and south.

European history is outlined in the Yalgorup National Park Management Plan (https://www.dpaw.wa.gov.au/images/documents/parks/management-plans/decarchive/yalgorup.pdf).

European History: WA Portland Cement Co. 1922

Extraction of Marl from Lake Clifton occurred from 1919 to 1921 lime marl (sand, clay and shells) was pumped from the bottom of Lake Clifton through a pipeline into settling ponds, where it was then loaded onto trucks and sent to the cement works at Burswood. Later a railway line was built and officially opened in 1921 to transport the raw material from Lake Clifton to Waroona and then on to the cement works at Burswood.

A rotary kiln was constructed in 1922 for the convenience of processing the lime marl at the site prior to transport. It operated for only 2 days and was then closed due to the inferior quality and unsuitable for cement manufacture.

Biotic

The current conservation values of the native vegetation and thrombolites may have suffered irreversible damage if the lime works had proved successful.

The area was cleared during the time of the building of the lime kiln.

Regrowth includes Peppermint (Agonis flexuosa) dominant woodland, with Tuart and banksia’s present.

The understory includes many native species of understory including terrestrial orchids.

Towards the edge of Lake Clifton is sedge land, samphire marsh that includes open low heath and very open herbland (Keighery & Keighery, 2013.)

This geosite will test your imagination.

The Waroona Tourist Visitor Centre has a store of infomration for you to learn more about this amazing town.

Also check out Waroona’s Drakesbrook Weir Dam. There is plenty of geology up there.

Geology

The geosite you are standing on is representative of the fault line that created the Darling Scarp. Imagine you have one foot either side of the fault line. Look to the east and see how far back the Scarp has eroded. The erosional detritus has contributed to filling the Swan Coastal Plain.

“After granite magmatism ended around 2600 million years ago, the Yilgarn Craton became stable. About 1400 million years ago a zone of deformation and mobilization developed on its western margin, and the Darling Fault was formed. Sedimentary rocks were deposited at the foot of the Darling Scarp that belong to the Cardup Group (Low, 1972; Playford et al., 1976) and consist of conglomerate, sandstone, siltstone, and shale. These sedimentary rocks are Proterozoic in age, possibly around 1400 million years old (Fitzsimons, 2003), and rest directly on the Archean granites of the Yilgarn Craton. They are unrelated to the sedimentary rocks in the Perth Basin”.

This information was extracted from Geology and Landforms of the Perth Region. There is much more so for further reading see pages 14-16: file:///E:/Libraries/Downloads/gsdpub_geology_and_landforms_perth_region.pdf

Culture

Although there is no firm evidence, it is likely Aboriginal groups travelled down from the Scarp along the Drakesbrook river to the Swan Coastal Plain according to an Ethnographic and Archaeology Report (https://www.epa.wa.gov.au/sites/default/files/PER_documentation/1510-PER-Waroona%20Aboriginal%20Heritage%20Survey.pdf).

Biotic

The native fauna in the Shire of Waroona is dependent on the native vegetation that once covered the area. The populations of many species have declined significantly since European settlement. However, there are numerous of mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, inland fish, invertebrates and subterranean fauna within the Shire (https://www.waroona.wa.gov.au/Assets/Documents/local-planning-strategy/Waroona-LPS.final.whole-document.pdf).

The Noisy Scrub bird was first recorded in the hills near here: Well known zoological collector John Gilbert discovered the noisy scrub-bird at Drakes Brook in the Darling Range in November 1842, while collecting specimens for ornithologist John Gould. The small brown bird was first brought to the attention of science through John Gould`s lavishly illustrated Birds of Australia, published in England in 1845. The species disappeared from the Darling Range soon after European settlement and was thought to be extinct until its rediscovery in 1961 at Two Peoples Bay near Albany. (Reference: https://monumentaustralia.org.au/themes/culture/animals/display/61209-noisy-scrub-bird)

This geosite is near the award winning Edenvale Heritage Precinct. There is amazing heritage interpretation and a tea room (https://www.edenvaleheritageprecinct.com.au/).

Geology

The Murray River has two major tributaries, the Hotham River, which starts near Narrogin and the Williams River, that starts between Williams and Narrogin. These are also the two main rivers which drain the eastern wheat-belt.

The Murray River flows through vegetated parts of the Darling Range to Pinjarra. The deposition of sediment from the Yilgarn and Darling Scarp has been deposited over a period of time and on the banks of the Murray River. Here you can see 4 different time periods of deposition from youngest Coolup, Wellesley, Boyanup and Blythewood (Seddon, 2004).

The right-angle bend in the Murray River occurs South of Coolup and then again north of Pinjarra. In the past the Dandalup River was the mainstream and the Murray River was a tributary. The river then flows across the coastal plain between the Darling Scarp to empty into the Peel-Harvey Estuary near Mandurah through a delta system of islands.

Culture

Murray River system is a regional significant waterway devoid of dams for public water supply.

The cultural story includes how the Waugal sent her young eastwards, creating the riverways. There are several cultural sites along the river and further consultation is needed for this site for cultural significance.

Biotic

Riparian vegetation: Flooded Gum trees (Eucalyptus Rudis) line many parts of the river, she-oaks (Casuarina obesa), and saltwater paperbark (Melaleuca cuticularis) also occur in the riparian vegetation. Standing dead vegetation includes (Melaleuca rhaphiophylla) which has been inundated by saltwater. Sedges and Saltmarshes line many low-lying edges of the river.

Fauna: Bottlenose dolphins, Rakali (native water rat) (Hydromys chrysogaster) Fish species: Fish Species: Yellowtail grunter, Cobbler, sea mullet, western hardyhead, pouched lamprey, black bream, Birds: waterbird, migratory and resident, bush birds and birds of prey. Species varies across the river ecosystems with up to 70 species observed.

The Geogrup Lakes System also known as Willy’s Lake is a large open shallow wetland (max depth approx 1.5 metres) covering 1700ha containing native vegetation along its banks, riparian salt marches, streams and small islands situated in a scenic river valley.

Albout 1700 ha, 50km to 65 km S of Perth, comprising the lower reaches of the Serpentine River & inc that portion of the river system that is composed of channels & open water bodies such as the Goegrup Lakes Chain, Yalbunberup Pool, Amarillo Pool & Guananup Pool & their surrounds (http://inherit.stateheritage.wa.gov.au/Public/Inventory/Details/ea71b2cb-1e74-4012-9e04-78af58897f89).

For further information see: https://library.dbca.wa.gov.au/static/Journals/082179/082179-06.pdf

Geology

The Serpentine River flows southward between Bassendean and Spearwood Dunes into a large open shallow basin called Lake Goegrup.

It is a permanent wetland formed approximately 10,000 years ago.

Culture

This area has a substantial number of significant Aboriginal sites.

It is highly significant to local Aboriginals as a place with significant resources in and around the lake.

The richness of the lake as a resource led to conflict between the local indigenous people and white European settlers. The narrow creek which joins Goegrup Lake to Black Lake was a site of a wooden fish trap (or mungur) and indigenous camps spread approximately 200 metres to the south-west and north-east of this Fish trap. It was known as Nambeelup. (O’Conner et al, 1989).

Biotic

Large shallow lake on the Serpentine River. Abundant water bird life, fish breeding area, and regular bottle nose dolphin hunting area.

The lake has extensive riparian temperate saltmarshes (TEC) and estuarine fringing forest.

Large numbers of waterbirds and international migratory shorebirds use the wetland for feeding and roosting.